Pain & Glory is a film I missed at TIFF on purpose. I wanted to wait to watch it alone. There is something so intimate about Almodóvar’s work specifically the warrants a completely quiet room to sit with and fully absorb the images being presented. He’s a director that I don’t always like but consistently respect, pushing the boundaries of what family drama can look like on the big screen. Each of Almodóvar’s films is like a vibrantly painted room in a vast familial estate. All fit into a larger emotional tapestry that becomes clearer the more pieces of his filmography you watch. All of his films are rooted in a sense of family; sometimes found, sometimes blood-related, always profound. An Almodóvar always makes me want to sit with my thoughts afterward, and that’s hard to do in a theater full of critics.

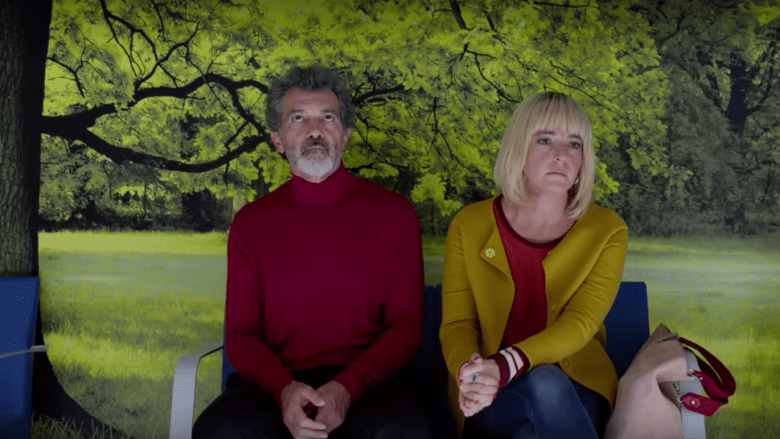

But by the time NYFF came around, my curiosity got the better of me. I’d sat through most of the festival waiting for a film to move me, and I knew Almodóvar could. Pain & Glory made me feel even more than I thought I would, opening the floodgates for a classic New York subway cryfest. Antonio Banderas has eyes more expressive than any actor working, portraying longing and regret with heart-pounding intensity. No one directs him like Almodóvar, and there’s something beautiful about the perfect symbiosis of their powers. Not since their previous collaboration The Skin I Live In has Banderas commanded the screen in a role that feels made for him.

Banderas plays Salvador, an aging director suffering from intense chronic pain. We meet him submerged in water, attempting meditation and pain management. During the Q&A at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater, Almodóvar said that he wanted the story to “flow like water”. And it does–memories flow through Salvador’s mind, triggered by conversations, thoughts, or sometimes just a look. Pain & Glory is a film that reminds us that past and present are consistently, and often painfully, linked. Flashback’s reveal Salvador’s early life with his mother (Penelope Cruz) and how her spirit ways heavy on him in the present. The film also flashes back to the time shortly before she died, revealing how his mother (played in old age by Julieta Serrano) reflected on her life and Salvador’s place in it. In the present, he reconnects with an actor from one of his most celebrated films (Asier Etxeandia) and finds a new vice: heroin.

Salvador takes to heroin as a distraction from the current state of his career. He’s in too much pain to direct and is generally wearied by his newfound role as a figure of film history. He wants to be part of film’s present, but he doesn’t think he’ll ever be able to create again. It seems as if he would rather allow himself to wither away, but his loved ones won’t let him. Salvador is a man surrounded by women who want to take care of him and haunted by his mother, a woman he never felt that he had taken proper care of. Almodóvar has always populated his films with strong women who lead rich, interior lives. The director seems constantly in awe of their strength, style, and sensuality. In contrast, the men in his films are often lost, in need of female guidance and direction.

This characterization of women is a bit limited, but there’s an honesty about it that feels true. Pain & Glory flows much better than his previous examination of motherhood, All About My Mother, a film that tries so hard to mean something that all the color and humor of his previous work drains out. In Pain & Glory, Almodóvar corrects that mistake by approaching motherhood through the eyes of a son. For better or worse, that is where he is most comfortable.